Prepared with Co-authors Thomas J. Taylor, PhD, and James Willits

Except in extremely arid climates, there is always some amount of water vapor in the air around us. When that air comes into contact with a cold surface, that water vapor condenses as a liquid onto the surface. A good example of this is the water droplets on the side of the glass of ice water. Those droplets are commonly known as "condensation" and are what results when the air gets too cold to hold the water vapor that is in it. Even when a cold surface is not available, if the air temperature suddenly drops, water vapor condenses out as mist or fog. Air can only hold so much water – more at higher temperatures and less at colder temperatures.

Let's examine this in a little more detail, taking a closer look at…

Relative Humidity

We know that air contains water vapor but we need to define how much it contains. At any temperature, there is a maximum amount of water that air can hold. When we measure how much water is actually in the air, we express the number as a percentage of that maximum amount. For most people, 50 to 60% relative humidity is very comfortable, but most of us can easily tolerate anywhere from 30 to 70%. Relative humidity below 30% is noticeably dry and above 70% is when people start commenting about how humid it feels.

Let's compare Miami and Phoenix to see how relative humidity comes into play. In Miami, a cold beverage may be served with a napkin wrapped around it to absorb the condensation that forms on the glass. But in Phoenix, there may be so little condensation on the cold glass that a napkin might not be needed. Why is that? Relative humidity is the major contributing factor. The reason is that the relative humidity in Miami is likely to be above 65%, i.e., the air is holding 65% of the moisture it is capable of holding. In contrast, the air in Phoenix would likely be dry with a relative humidity around 35%, causing very little condensation to form. So, to recap, relative humidity is a ratio of how much water vapor is in the air in relation to how much the air can contain at a given temperature. The "relative" part refers to the fact that air's capacity to hold moisture changes with temperature. The warmer the air is, the greater amount of moisture it can hold. The more moisture it holds, the greater the volume of condensation forms on a cold surface. Now, let's discuss dew point.

…air's capacity to hold moisture changes with temperature.

Dew Point

The dew point is a specific temperature at a given humidity at which water vapor condenses. Let's consider Miami and Phoenix again as two extremes. In the summer, Miami's relative humidity can reach 85% at a temperature of 80°F. Obviously, a lot of condensation will form on a chilled beverage glass. But it actually does not take much of a drop in temperature to reach 100% relative humidity and have condensation form. So, a lot of cool surfaces will have condensation on them. At the same temperature in Phoenix (80°F), the relative humidity could be 35%. The temperature would have to be much lower before condensation could form. Cool surfaces would not have condensation on them.

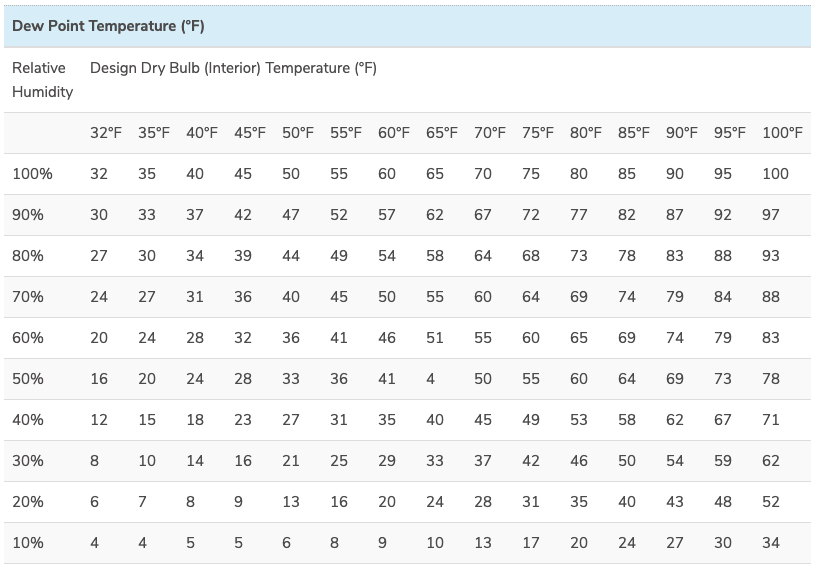

The Dew Point is the temperature at which condensation forms. It is a function of the relative humidity and the ambient temperature. In other words, the amount of water vapor that is in the air and the temperature of the air. Take a look at the chart below (which is a very simplified form of what is actually used by HVAC engineers). Let's pick the 40% relative humidity line in the first column, and follow that line across to the 70°F column. The 40% line and 70°F column intersect at 45°F, meaning that in an environment that is 70°F and 40% relative humidity (RH), water in the air will condense on a surface that is 45°F.

Dew Point Temperatures for Selected Air Temperature and Relative Humidity

Chart adapted from ASHRAE Psychometric Chart, 1993 ASHRAE Handbook—Fundamentals.

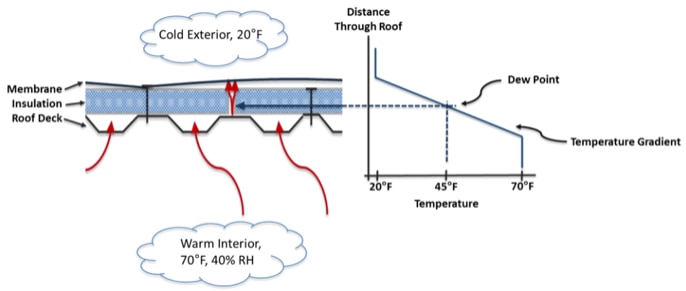

So, what does that have to do with roofing? Well, consider your building envelope: It separates the interior conditioned environment from the outside. The foundation, walls, and roof are all systems that intersect to make this happen. Although this pertains in some respect to all of the systems, we will focus on roofing. The insulation layer in the roofing system resists heat loss or gain from the outside, depending on the season. Within the insulation layer, the temperature slowly changes until it reaches outside. Let's talk about a building in the winter to illustrate the point. The interior is 70°F with 40% RH, like our example on the chart above. As you move through the insulation layer from the inside toward the outside, the temperature gradually drops until it reaches the colder temperature outside. The plotting of those temperatures is referred to as the temperature gradient of that system.

Now, if the temperature gets to 45°F at any point in that system (the dew point temperature on the chart), then water would be expected to condense on the nearest surface. This is shown in the following diagram:

To recap, the interior air has 40% of the total water vapor that it can support. But as the air migrates up through the roof system, it gets cooler until the point where it can no longer hold on to the water vapor and condensation occurs. In the example shown above, this would happen at 45°F and just inside the insulation layer.

Lessons for the Roof Designer

Condensation — which is liquid water — can negatively affect the building in many ways. It can lead to R-value loss of the insulation layer by displacing the air within the insulation with water, as well as premature degradation of any of the roofing system components, such as rotting wood or rusting metal (including structural components). It can also contribute to unwanted biological growth, such as mold.

However, prevention of these negative effects is possible. Remember that water vapor needs to get to a surface or location that is at or below the dew point temperature.

In the schematic of the roof assembly shown above, it is clear that interior air must be prevented from moving up into the roof as much as possible. This was discussed in detail in an earlier GAF blog. One method to limit air movement into a roof includes using two layers of overlapping foam insulation. Another method is to place a vapor retarder or air barrier on the warm side of the insulation. The vapor retarder/air barrier can prevent the water vapor from reaching the location where it can condense.

Also, penetrations for vents and other details that involve cutting holes through the insulation must be looked at closely. If the gaps around penetrations are not sealed adequately, then the interior air is able to rapidly move up through the roof system. In cold climates that may lead to significant amounts of condensation in and around those penetrations.

Additionally, the billowing effect of a mechanically attached roof can exacerbate the potential for condensation because more air is drawn into the roof system. An adhered roof membrane may help limit the potential for air movement and subsequent condensation.

One important thing to remember is that relative humidity, and interior and exterior temperatures in summer and winter, should be considered when designing the envelope.

Typically, commercial buildings have an environment designed by an HVAC engineer that will determine interior temperature and relative humidity taking occupant comfort into account, as well as a design exterior temperature based on the weather in the building's location. These and other factors help engineers determine what type and size of equipment the building requires. The building envelope designer will use those values, plus the designed use of the building, and local codes to determine the construction of the building envelope. One important thing to remember is that relative humidity, and interior and exterior temperatures in summer and winter, should be considered when designing the envelope. An envelope design that works in one area of the country may not work in another part of the country which could lead to adverse conditions and the types of degradation mentioned earlier. Consider how your wardrobe would change if you moved from Minneapolis to Phoenix (here, we are relating your clothes to the building envelope).

In a perfect world, the location of the building would be the entire story. Unfortunately, building use can (and often does) change. Factors that can adversely affect temperature and humidity, and therefore hygrothermal performance of the envelope, can include: a dramatic change in the number of occupants, the addition of a kitchen or cooking equipment, the addition of a locker room workout area or shower, and sometimes even something that seems insignificant like an aquarium or stored wood for a fireplace. This is not meant to be an exhaustive list, but a few illustrative examples to communicate a general understanding. Believe it or not, even changing the color of the exterior components could contribute to greater or less solar gain and effectively change the dew point location within the building envelope.

Changing the dew point and/or dew point location can lead to unwelcome condensation, and potentially result in damage.

Consider a situation where an owner decides to invest in energy efficiency upgrades on their property while replacing the roof. The owner upgrades windows, doors, and weather-stripping at the same time. The building could have had latent moisture problems that were previously hidden by air leaks across the building envelope. After the retrofits, those issues may surface, for example, in the form of stained ceilings. Was the water damage caused by the retrofit? Most likely the answer would be no. The previous inefficient design disguised the problem.

Keep in mind that a holistic approach should be taken with building envelope design. If you change one part, it could negatively affect something else. This blog is for general information purposes only. It is always a good idea to consult a building envelope consultant to help prevent condensation issues and ensure that small changes do not become large problems.